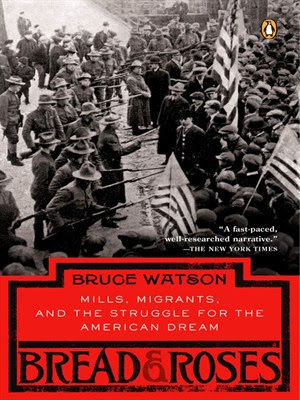

Bread & Roses by Bruce Watson

This review originally appeared in the January 2006 issue of Z Magazine. I'd forgotten about it until somebody today mentioned that it's the anniversary of most of the striking workers' demands being met (12 March 1912), and so today seemed like a good one to post this:

by Bruce Watson

New York, Viking,

2005, 337 pp.

Lawrence, Massachusetts was, at the beginning of the

twentieth century, what might be called one of the greatest mill towns in the

United States, but "greatest" is a difficult term, and underneath it

hide all the conditions that erupted during the frigid winter of 1912 into a

strike that affected both the labor movement and the textile industry for

decades afterward.

Bruce

Watson's compelling and deeply researched chronicle of the strike takes its

name from a poem and song that have come to be associated with Lawrence, although

there is, according to Watson, no evidence that "Bread and Roses"

ever appeared as a slogan in Lawrence until long after 1912. This fact might suggest that Watson's

position is one of a debunker, but he offers less debunking than revitalizing,

and the ultimate effect of his book is to show why the romantic notions behind

the "Bread and Roses" phrase do a disservice to the courage and

accomplishments of the strikers.

Watson's greatest strength is his ability to weave weighty research into a narrative that is lively and seldom ponderous. There are costs to this approach, because the minutia of a strike's planning and execution are not always suspenseful, and so, as Watson strives to hold the reader's interest there are times when the sentences sound like the narration of "America's Most Wanted" and swaths of yellow from the journalism of 1912 seem to have seeped into the book's pages. This is a minor annoyance, though, in a book filled with vivid portraits of ordinary workers and their families, and with precise, careful renderings of an age and culture. Again and again, Watson brings the book back to the circumstances of the immigrant workers who started the strike, and he compares their lives to those of other workers throughout the United States, to the owners and administrators of the mills, to the politicians, to the police and the soldiers who were sometimes fierce combatants with the strikers, sometimes bewildered and beleaguered sympathizers.

It would be

interesting to watch a free-market ideologue respond to Bread and Roses, because again and again Watson presents damning

evidence of the failures of unbridled capitalism to produce anything but misery

for people who worked in the mills. He

includes a budget created by one of the workers' wives; she lists such expenses

as rent, kerosene, milk, bread, and meat.

Watson lays out the family's other expenses, the fact that they couldn't

afford to buy coal and so their only heat during the brutal winters came from

the bits of wood their children could scavenge, the luxuries they couldn't buy

(butter and eggs), and then comments: "Like most mill workers, the Bleskys

could not afford clothes fashioned in Manhattan sweatshops from fabric made in

Lawrence. ... The Bleskys each wore the same clothes until

they wore out. When the strike began,

Mrs. Blesky was still wearing the shawl, skirt, and shirtwaist she had bought

in Poland three years earlier, just before coming to Lawrence. Ashamed of her shabby appearance, she almost

never left her home."

Searching

through numerous archives, Watson has unearthed one story after another like

this one, and each undermines the fanciful justifications and accusations made

by the mill owners, which Watson also chronicles well. To his credit, though, he does not present

the owners, the politicians who supported them, and the reporters who often

printed even their most outrageous lies as caricatures, creatures so obsessed

with profit that they would happily trod over the people who created that

profit for them. Instead, he tries to

divine the self-delusions and paranoid fears that motivated the workers' many

antagonists. While on the surface it may

seem immoral to try to portray the masters of such misery as flawed and

idealistic human beings, the result is both complex and useful, because

ideology was as much a part of what created the misery as was greed.

The

Lawrence strike became a national cause, and it attracted the attention of

celebrities and rising stars of the labor movement, including Big Bill Haywood

and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn of the IWW and John Golden of the AF of L. The events and tactics that brought so much

attention to Lawrence are particularly fascinating, and Watson does an

admirable job of showing how the strikers decided to carry out the strike and

advance their cause, particularly with the controversial and immensely

effective "children's exodus", where the children of strikers were

sent to the homes of union members in New York, Vermont, and elsewhere. With each new day and week of the strike, more

groups joined in, until the strike itself became, for a short time, a panoply

of people from all around the world.

Numerous women, too, who had often been relegated to the background in

labor struggles before, became vital players in Lawrence, and the book includes a marvelous photograph

of a parade of women holding their hands high, joyous smiles on their faces as

they march down the street, defying the martial law imposed on the city.

Even as more and more strands are

added to the story, the tale itself stays clear. Watson manages to show how the different

segments of the labor movement both aided and undermined each other, and he

doesn't smooth over the conflicts that broke out when the national interests were

different from the local ones. (On the

whole, though, this strike was remarkably unified compared to others both

before and after it.) Haywood and Flynn

in particular make for great characters in the story, but Watson skillfully

keeps them from stealing the stage, always bringing the story back to the lives

of the workers in Lawrence, the people who would have to live with the

consequences of the strike once the nation's interest turned to other events.

In the end,

it is the ordinary workers who remain the most remarkable element of the Lawrence

strike, as Watson tells the story, because here were people from vastly

different backgrounds, experiences, religions, and even political views who

found solidarity and, through this solidarity, a certain amount of success. The epilogue is not misty-eyed about the

effects and consequences of the strike, but it also offers a kind of quiet hope

for the future: for all the possibilities that imaginative, energetic, and

compassionate mass action can create.